Pathogenic variants in the ELMO2 gene cause intraosseous vascular malformations mainly in craniofacial region (Figure 1 and Figure 2). For detailed information: Vargel et al, 2002; Çetinkaya et al, 2016.

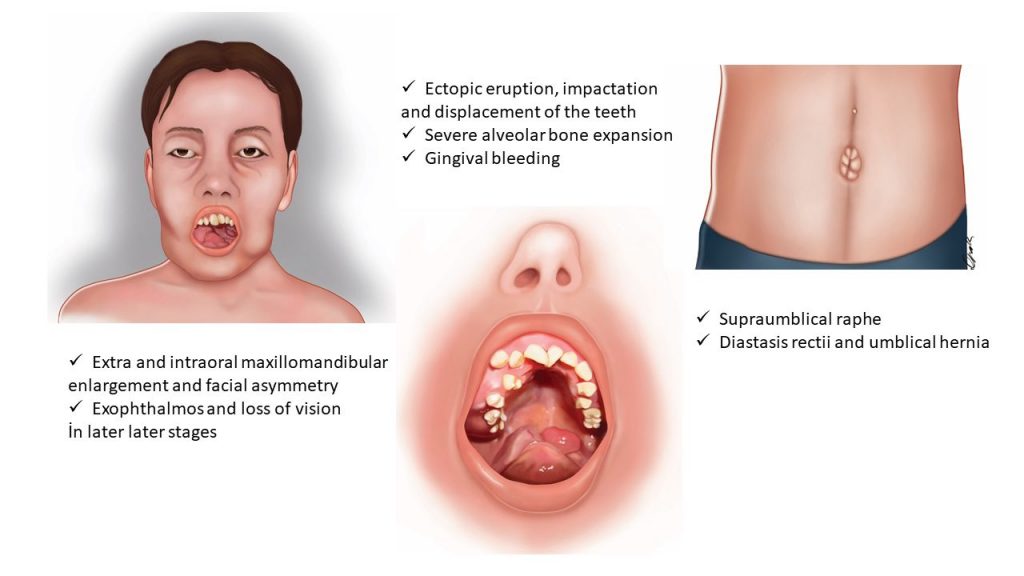

Figure 1. Illustration of morphological characteristics of the VMOS.

Figure 1. Illustration of morphological characteristics of the VMOS.

Bony Lesions

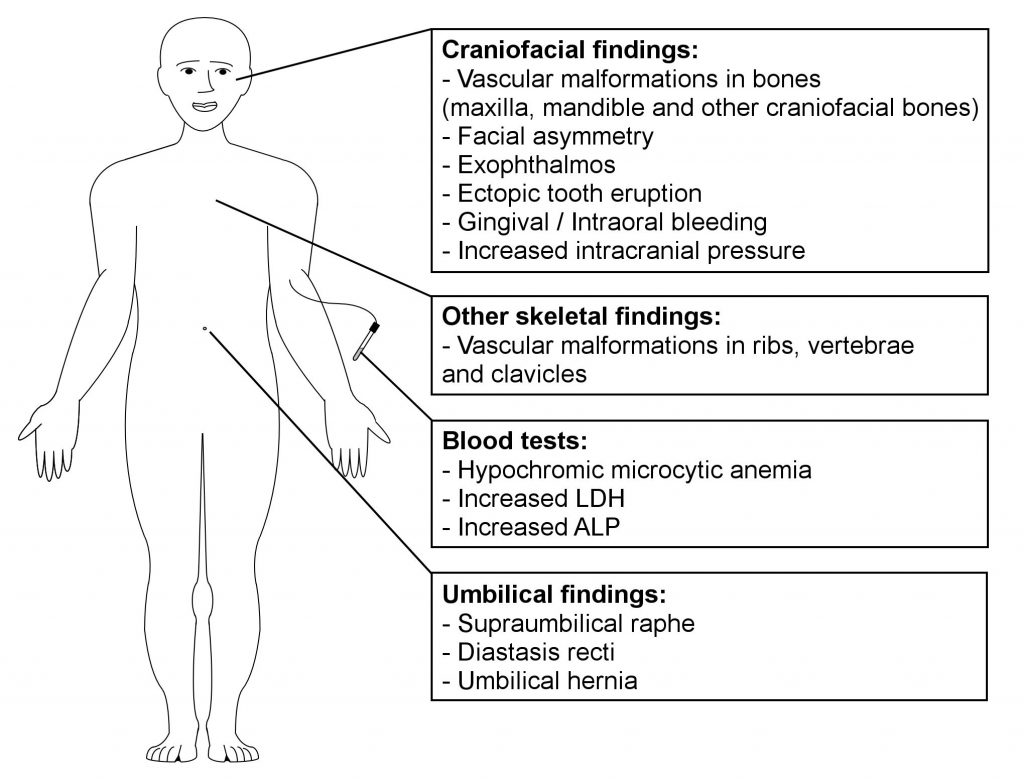

The most striking feature of VMOS is primary vascular malformation in craniofacial bones. The malformations that appear as multiple swellings of the facial bones that slowly progress through months/years are usually the first findings noticed by the families. Alternatively, slow or massive gingival bleeding would alarm the families to seek medical assistance. The affected bones always include the mandible and maxilla in all affected individuals, presented until today and may involve nasal bones, calvaria, sphenoid, and clivus. Usually the swellings appear in the mandible and maxilla prior to onset of puberty. However, they propagate to other craniofacial bones and the progression accelerates during puberty. Some affected individuals also show increased levels of blood alkaline phosphatase (ALP), suggestive of increased bone turnover.

The intraosseous lesions seem to spare appendicular skeleton and pelvis, but small lesions have been observed in clavicles, ribs, and vertebrae. The adult tooth eruption is usually severely affected, which leads to ectopic teeth, maloclusion and eating problems.

Hematological Findings

The patients may suffer from chronic anemia which is characteristically microcytic and hypochromic. The anemia is thought to appear as a result of chronic bleeding from intraoral vascular lesions. However in some affected individuals it is accompanied by elevation of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, indicating intravascular hemolysis due to blood cell damage passing through malformed vessels.

Other Findings

The irregular swelling of the craniofacial bones may obstruct and disturb several structures of the head. Obstruction of paranasal sinuses may lead to frequent episodes of sinusitis. Crowding of the orbital cavity may lead to varying degrees of exophthalmos and loss of visual. Occupation of intracranial space and obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid may lead to increased intracranial pressure.

Important extraskeletal findings which are not present in every affected individual but may hint VMOS are the umbilical abnormalities. Umbilical hernia, diastasis recti and supraumbilical raphe are must be inspected during physical examination.

Figure 2 . Clinical features of individuals with VMOS.

Radiological Findings

The radiological appearance of swellings is an important, but not specific first step in evaluating individuals with suspected VMOS. Computed Tomography (CT) scans of head and neck region always show expansion of several craniofacial bones, especially maxilla and mandible, which is progressive over years. Obliteration of paranasal sinuses and exophthalmia may be observed, resulting from asymmetric disturbance of overall bone anatomy. The bone lesions appear as cavern-like low density areas accompanied by cortical thinning and absence of soft tissue involvement. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) shows bone involvement as heterogeneous hyperintense lesions on T1-weighted images including multiple, scattered, low signal intensity, round areas, which are contrast-enhanced. On T2-weighted and FLuid Attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR) MRI images, high signal intensity of the involved bones are seen and the contrast enhancing cavern-like areas appear homogeneously hyperintense. CT and MRI may be especially useful in determining the extent and location of VMOS lesions. However, the intraosseous vascular malfomations may be indistinguishable from other lesions in bones such as fibrous dysplasia or multiple craniofacial fibrous dysplasias (cherubism) by conventional X-rays, CT and MRI.

Cerebral angiography is a more accurate method for differential diagnosis of VMOS as it shows the capillary/venous nature of the lesions. VMOS lesions appear as abnormal multilocular bony stainings branching from external carotid arteries. The lesions show late-phase pooling of contrast material. The arteries that supply the lesions may be enlarged (Vargel et al., 2004).

Pathological Findings and Differential Diagnosis

The facial appearance of individuals with VMOS and their CT images resemble cherubism which is the hereditary form of fibrous dysplasia of the craniofacial region, (OMIM #118400). Thus, pathological findings are critical for differential diagnosis since there are no pathognomonic radiographic findings.

Histological appearance of VMOS lesions show irregular, thin-walled, dilated, and engorged vascular channels lined by a single layer of ECs with low mitotic activity. The surrounding vascular smooth muscle cell layer is also thin and can show a lack of maturity markers of differentiation such as desmin and h-caldesmon. It is also imperative to observe the amount of fibrous elements in the tissue as fibrous tumors of the bone can be challenging to differentiate by clinical and radiological findings. Histological absence of abundant cellular fibrous tissue between bone trabeculae rules out fibrous tumors.

Regarding vascular anomalies, various terms have been used to describe malformations similar to VMOS, including intraosseous cavernous hemangioma, extraspinal osseous hemangioma, central hemangioma, cavernous angiomata of skull, and cystic angiomatosis. However, pathological examination and classification of these lesions are obscure and these definitions are usually based on the clinical and radiological findings instead of histological examination of tissue.

The International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) classifies vascular anomalies into two major categories: tumors and malformations, according to their clinical behavior and endothelial properties. Vascular tumors are characterized by actively proliferating neoplastic ECs, whereas vascular malformations are non-neoplastic abnormal expansions of vascular tissue, without prominent endothelial proliferation. Thus, terms including hemangioma, which refer to vascular tumors are inappropriate for VMOS lesions and must be avoided.

Variable expressivity

The severity of the clinical features is variable among individuals with VMOS even in siblings having the same ELMO2 mutations. For the time being, it is not possible to predict beforehand the growth speed and exact location of vascular malformations.

Prognosis

In the course of follow-up from when the first 2 families with hereditary VMOS were reported in 2002 until mutations in ELMO2 were pinpointed as the genetic cause of VMOS in 2016, the craniofacial malformations in the affected individuals continued to gradually increase in size and spread. For 2 individuals, VMOS was proved to be lethal due to spontaneous massive bleeding through bony lesions at age 27 and brain stem herniation at age 36 due to increased intracranial pressure.